Consensus in Distributed Systems

Consensus is the problem of getting multiple nodes to agree on a single value in a distributed system. It’s everywhere in databases, blockchain, microservices, and distributed databases. Yet it’s one of the hardest problems in computer science.

“How can two walk together, except they be agreed?” - Amos 3:3

This ancient wisdom captures the essence of distributed systems. When multiple nodes need to coordinate, they must reach agreement. But in a world where messages can be lost, nodes can fail, and networks can partition, achieving this agreement becomes one of the hardest problems in computer science.

The philosopher Epicurus once said that “the art of living well and the art of dying well are one.” In distributed systems, we might say that the art of agreeing and the art of failing gracefully are one. Consensus algorithms must be designed not just for success, but for graceful failure when the impossible becomes reality.

Why this stuff matters

Consensus is fundamental to distributed systems. Without it, you get split-brain scenarios where different parts of the system make different decisions. This leads to data corruption, inconsistent state, and system failures.

Think about it in real-world terms. When you have database replication, all those replicas need to agree on the same sequence of operations. When you need to elect a leader in a distributed system, all nodes have to agree on who that leader is. When you’re committing a transaction across multiple nodes, they all need to agree to commit or abort. And when you’re changing system configuration, every node needs to agree on the new settings.

The fundamental challenge is that consensus is impossible in asynchronous systems with even a single failure. This is the Fischer-Lynch-Patterson impossibility result. But we still need consensus in practice, so we use algorithms that work most of the time.

The Two Generals Problem

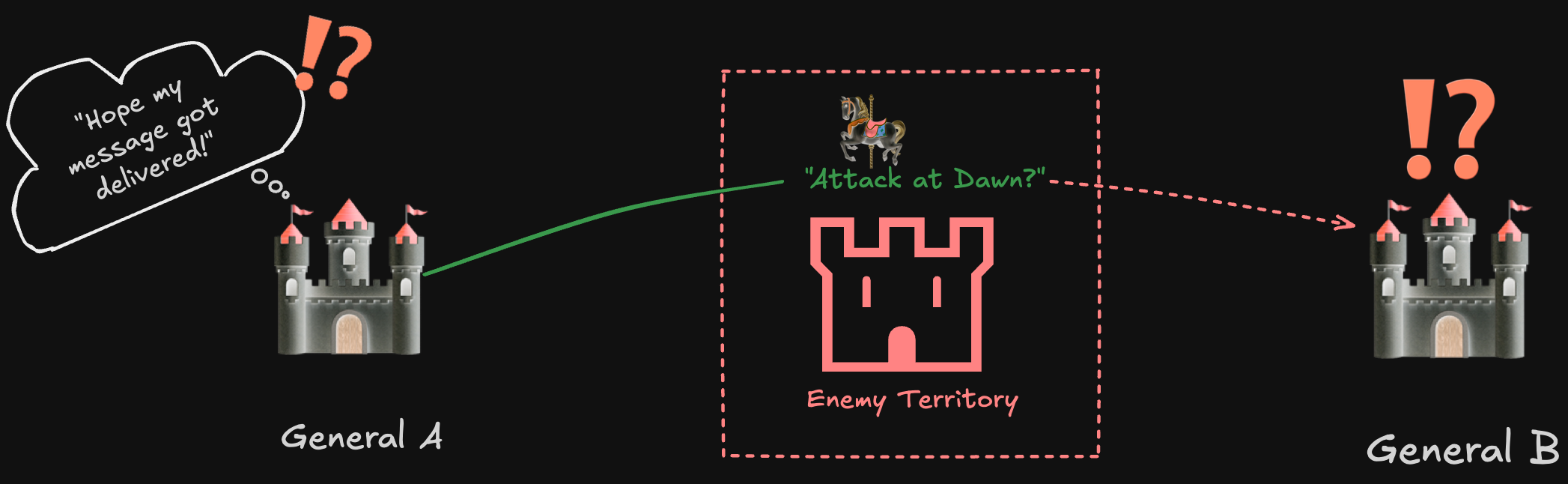

To understand why consensus is so hard, let’s look at the classic Two Generals Problem. It’s a thought experiment that reveals the fundamental impossibility of reaching agreement in unreliable networks.

Two generals are on opposite sides of a city. They need to coordinate an attack. If they both attack together, they win. If only one attacks or they attack at different times, they lose. The generals can only communicate by sending messengers through enemy territory.

Here’s the catch though: messengers can be captured, messages can be lost, and generals can be traitors who send false messages.

Here’s where it gets messy

General A wants to attack at dawn. He sends a messenger to General B with the message “Attack at dawn.”

But what if the messenger gets captured? General B never receives the message. General A doesn’t know if B received it or not. If General A attacks without knowing B’s status, he might attack alone and lose.

So General A needs confirmation that B received the message. But here’s where it gets tricky.

The catch-22

Let’s say General A sends “Attack at dawn” to General B. General B receives it and sends back “I received your message, I will attack at dawn.”

But what if this confirmation message gets captured? General A is stuck. He can’t know for certain that B received the message, and he can’t attack without knowing B’s status.

So General A sends another messenger: “Did you receive my attack order?” But what if this messenger also gets captured? General A is stuck in an infinite loop of uncertainty.

This is the fundamental problem: you can never be certain that a message was delivered in an unreliable network.

But wait, if consensus is impossible? how do distributed systems actually work? How do databases stay consistent? How does blockchain reach agreement?

The thing is, the Two Generals Problem assumes the worst possible scenario: a completely unreliable network where anything can go wrong. In real life, we cheat a little bit.

So how do we actually make it work?

The Two Generals Problem proves that consensus is impossible with even one faulty process in an asynchronous system. You need three things to work together: safety (everyone agrees on the same value), liveness (everyone eventually decides), and fault tolerance (works even when things break).

In the two generals scenario, if General A can’t tell if B got the message or not, he’s stuck. Wait forever and you violate liveness. Attack without knowing and you violate safety. Classic catch-22.

But here’s the thing. The impossibility result assumes everything can go wrong: messages can be delayed forever, any process can fail at any time, and no clocks or timeouts are allowed.

In practice, we relax these assumptions. We assume networks are mostly reliable and failures are mostly temporary. This lets algorithms like Paxos and Raft actually work in real systems.

What this means in practice

This isn’t just theoretical. The Two Generals Problem explains why databases can’t guarantee consistency if you have a distributed database, you can’t guarantee that all replicas have the same data. Network partitions can cause split-brain scenarios.

It’s why blockchain needs proof-of-work. Bitcoin uses proof-of-work to solve the consensus problem by making it computationally expensive to be a traitor. And it’s why microservices are eventually consistent when you update data across multiple services, you can’t guarantee immediate consistency. You have to accept eventual consistency.

In distributed systems, each consensus decision is unique and irreversible, shaped by the failures that preceded it.

Real systems that actually work

Since perfect consensus is impossible, we use practical solutions that work most of the time. These algorithms power some of the most important distributed systems today.

Take Kafka, for example. It uses a leader-follower model with majority voting for partition leadership. When a broker fails, the remaining brokers use consensus to elect a new leader for each partition. This ensures that messages are never lost and the system remains available.

Kubernetes uses etcd, which implements the Raft consensus algorithm, to store cluster state. All API servers must agree on the current state of pods, services, and configurations. Without consensus, you’d have different nodes thinking different things about the cluster. I’m actually building my own Raft implementation right now, which is supposed to be simpler than Paxos but we’ll see about that.

Distributed databases like CockroachDB and TiDB use consensus to ensure all replicas have the same data. When you write to one node, the system uses consensus to replicate that change to all other nodes.

And then there’s blockchain. Bitcoin uses proof-of-work as a consensus mechanism. Miners compete to solve cryptographic puzzles, and the longest chain represents the agreed-upon history. Ethereum is moving to proof-of-stake, which uses economic incentives instead of computational work.

I built a visualization of Paxos, one of the practical solutions to consensus: go-paxos. You can watch how nodes reach agreement despite failures.

The Two Generals Problem is a classic thought experiment in distributed systems theory. The Byzantine Generals Problem (which extends this to multiple generals) was formalized by Lamport in 1982 and is one of the most important results in distributed systems theory.